New readers of this blog should begin with the first post—"Introducing Miller's Five Principles of Pastiche"—at the bottom here and work their way up.

Recall that I’m writing this blog and these individual posts to help certain potential readers come to terms with my unconventional pastiche style before they buy or commit, or even open, my books. Those strongly expecting a linear plot with Dr. Watson calmly recording a remarkable Holmes thriller with Holmes at the top of his deductive game—which I dare say accounts for perhaps 98% of the endless tsunami of Holmes pastiches that have been published during the last 40 years—can only be hopelessly disappointed.

Recall that I’m writing this blog and these individual posts to help certain potential readers come to terms with my unconventional pastiche style before they buy or commit, or even open, my books. Those strongly expecting a linear plot with Dr. Watson calmly recording a remarkable Holmes thriller with Holmes at the top of his deductive game—which I dare say accounts for perhaps 98% of the endless tsunami of Holmes pastiches that have been published during the last 40 years—can only be hopelessly disappointed.

This

second post, then, describes the second of my five fundamental principles that

I used over 30 years while crafting the three books of my “Holmes Behind the

Veil” series. Recall that the first principle was that my books drew as much

from H. Rider Haggard as they do from Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes.

The

second principle stated that pseudo-prefaces, introductions, framing devices,

footnotes, and scholarly asides would not be peripheral to my work, but have

the uttermost prominence. To put this into perspective, during a period of 14 years, I crafted

Book 2 and especially its front matter slowly and carefully and made a

multitude of conscious, very deliberate decisions.

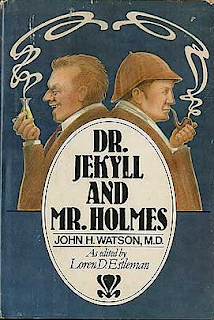

Now

that that is stated, there’s no point beating around the bush: while Book One’s

front matter amounts to 12 pages, on a par with the seminal works of Nicholas Meyer

and Loren D. Estleman, Book Two sports a contents page with the following list

of front matter, amounting to 66 pages:

Dedication

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Editor’s

Note to the Fourth Edition . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Editor’s

Note to the Third Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Editor’s

Note to the Movie Tie-In (Second) Edition . . . . . . 17

Preface: “The Prodigious Phone Call” . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Foreword by John H. Watson, M.D. . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Record

of A.Q.’s narration concerning certain

adventures that unfolded in east Africa during

the early part 1872, as set down by

John H. Watson, M.D. Feb. 1881. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . 53

Introduction

by Allan Quatermain. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

I ALLAN’S UNWANTED

GUESTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

The

reaction to this approach has mainly fallen into two clear camps:

On

one hand, in 2005 the staid industry journal Publishers Weekly blew it all off without a moments hesitation, saying

simply, “After a lengthy introduction that explains how the manuscript of the

present tale came to light, the main narrative….”

On

the other hand, several reader reviews back then were quite positive, seven

giving it five stars. I am especially fond of this classic from one “Golden

Fleece”:

“The true joys of this book lie in its

tendencies toward the epistolary. Quatermain has an epic adventure in which he

crosses paths with our itinerant hero Holmes; however, Quatermain's narrative

is actually ‘revealed’ several times over in the course of the document's

existence…In other words, the real story lies in the front material and the

editor's notes to the text. Not reading this material does the reader a

terrible disservice. I found the book to be very entertaining and difficult to

put down… This little exfoliate especially provided me gratification as I

sifted through its many layers because of its qualities as a ‘lost’ story that

is discovered and revealed through happenstance and vision.”

These

then are the facts; we now come to the point where I need to justify this

approach.

|

| 1974 |

|

| 1980 |

So

when, beginning in 1983, I started composing (see Post # 1) Sherlock Holmes on the Roof of the World,

which is Book One of my “Holmes Behind the Veil” series, I scrupulously made

sure there was sufficient realistic found-document front matter—12 pages.

I

was delighted when three otherwise educated, bright people came up to me over

the years and asked if the account I recorded actually happened. Naturally, in

order for this to have been the case, these individuals of necessity had to

believe that Sherlock Holmes was a real person.

It

took four years to get Book One ready for press, and by the time it was

published, it was all too evident that there was no standard whatsoever by

which pseudo-front matter was created, let along attached to various pastiches.

As

I spent the next 14 years sculpting what is now Book Two, I was prompted not by

commercial considerations so much as by irritation that authors and/or editors

chose to ignore the little gems that could and should precede pastiches, and

which I so thoroughly enjoyed. A pastiche without some sort of preface,

foreword, or introduction was only half written in my view.

Insofar

as there was never enough pseudo-front matter for my tastes, I made up my mind

to create a pastiche comprising “found documents” that absolutely depended on

realistic, detailed and significant front matter, materials laying out a scenario

that would be impossible to ignore, and which would be absolutely crucial to

the plotting and denouement of the story. The manner I did this was to pretend

that the book in its current state had gone through multiple editions with

separate introductions prefacing each one. In addition, I felt that the conceit

of multiple editions would enhance the novel's verisimilitude in the same

manner that Meyer had intended for his "foreword"— but taken to the

next level! In other words, the book would pretend to be a serious—almost

scholarly—compilation of "found" texts with appropriately detailed

explanations of their provenances.

|

| 1979 |

|

| 1978 |

And

while I was at it, I decided to incorporate a special, again ironic, touch. When

I was in school, I was greatly influenced by the works of some writers who

sometimes wrote their fiction as a sort of circle with the ending at the

beginning, and it came natural for me to follow suit. Thus the whole point of Book

Two is right there on page 8. All the action and the plot and the many twists

and turns and quests are resolved on the first page following the contents page.

Of course, this is often missed, especially since that “Editor’s Note to the

Fourth Edition” seems dry to many readers. Well, dryness was the whole point.

Yet,

here is the penultimate irony. Our culture does not reward interest in front matter,

regardless of the nature of the book. Whether starting a book of popular

science or an anthology of short stories, readers today simply ignore and skip over the front

matter.

And

finally, as perhaps a sad commentary on my naïveté, all those years I was

writing the book, it never once dawned on me that some readers might find my

style daunting. I imagined readers would quickly realize that my second

Holmes/Haggard pastiche needed to be approached with other-than-ordinary

expectations. Once it was published, however, I learned quickly that many

readers, though thank goodness not all as pointed out above, could not relate to the book. It was

much too far outside their comfort zone. One lady in my church said to me,

"It's rather like a study book isn't it?" I still cringe when I remember that! She thought it was a textbook! And to

my overwhelming astonishment, the reviewer for Publishers Weekly quoted above

simply did not “get” my book any way, shape, or form, despite my believing then

and now, that I wrote in a manner that careful readers would understand simply

by ignoring preconceptions, by recognizing the multitudinous clues I'd dropped

before page 8, and by applying a little common sense.

Therefore, you can easily see why I mentioned to my publisher that there needed to be some way to help readers "get" my approach to our overall "Holmes Behind the Veil" series. Hopefully this blog will aid in pulling off that trick!

Therefore, you can easily see why I mentioned to my publisher that there needed to be some way to help readers "get" my approach to our overall "Holmes Behind the Veil" series. Hopefully this blog will aid in pulling off that trick!

The

first book in the series is being released in June and available from all good

bookstores including Amazon

USA, Barnes

and Noble, and Amazon

UK.

Next: In my next post, I’ll focus on the important yet subtle role of fate in my pastiches.

Formal Notice: All images, quotations, and video/audio clips used in this blog and in its individual posts are used either with permissions from the copyright holders or through exercise of the doctrine of Fair Use as described in U.S. copyright law, or are in the public domain. If any true copyright holder (whether person[s] or organization) wishes an image or quotation or clip to be removed from this blog and/or its individual posts, please send a note with a clear request and explanation to eely84232@mypacks.net and your request will be gladly complied with as quickly as practical.

Formal Notice: All images, quotations, and video/audio clips used in this blog and in its individual posts are used either with permissions from the copyright holders or through exercise of the doctrine of Fair Use as described in U.S. copyright law, or are in the public domain. If any true copyright holder (whether person[s] or organization) wishes an image or quotation or clip to be removed from this blog and/or its individual posts, please send a note with a clear request and explanation to eely84232@mypacks.net and your request will be gladly complied with as quickly as practical.

No comments:

Post a Comment